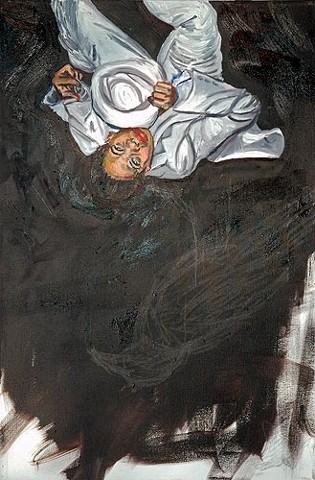

Sambo Scratches His Navel and Watches His Crazy Sister (2006-2009)

Statement

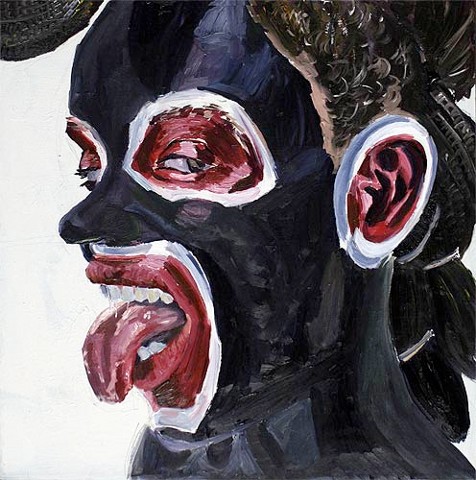

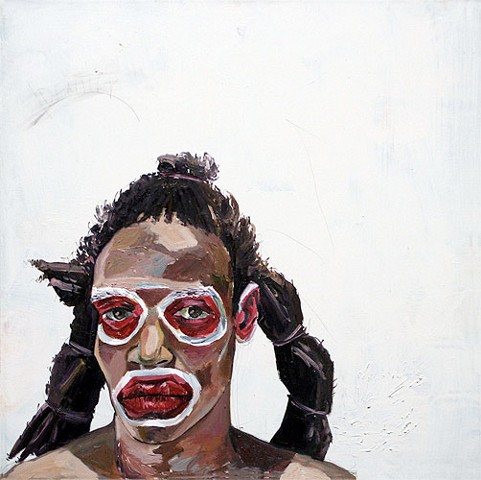

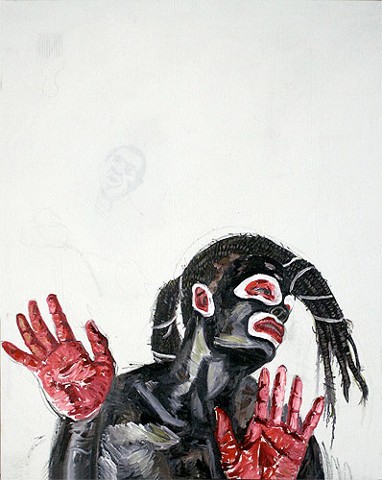

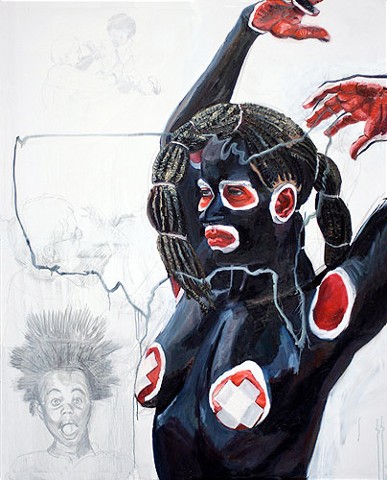

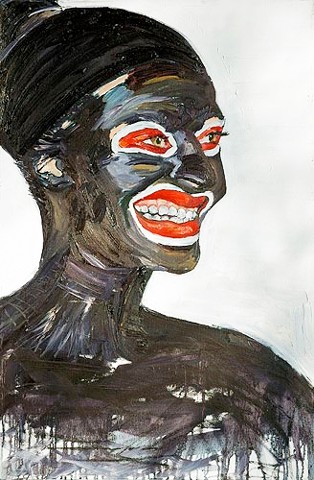

I first experienced Onye Ozuzu's performance of the Minstrel Mask at the Boulder Fringe Festival in 2005. She had painted her entire body black along with several red and white cirlces and performed on a circular stage stretched with canvas. This earlier rendition of the dance started slowly and as its speed and intensity increased it seemed as though she was trying to break free from the exterior identity that held her trapped beneath its blackness. Onye was trying to reclaim herself. I felt that this was a perfect metaphor for the struggles that I, and many others, have experienced as bi-racial people. I often say, "I am white around my black friends and black around my white friends," to explain how I relate to the world. I find myself not quite fitting in amongst most racially identifiable groups. This is the space that I live in, and what I paint about in my work.

Onye had viewed some of my earlier work in which I was using the Sambo figure, blackface, and whiteface to talk about race and identity. We started a two-year dialog about how we could bring our similar imagery together. The dialog led to this current collaborative body of work, Sambo Scratches His Navel and Watches His Crazy Sister. Most of the imagery that I have used in the paintings comes from Onye's dance performance titled, The Minstrel Mask (2006), but I have added new imagery with subsequent performances. Our ideal goal is to have the viewer experience both the performance work and the 2D work in the same space. We desire to transform and push the boundaries of the traditional art experience for the viewer and create new possibilities for collaboration amongst different art disciplines.

I see this collaboration as a reflection on a shared history and a shared experience that many bi-racial people are intimately involved. Identity is a combination of how you see yourself and how others perceive you. When these two identities align, the self and the perceived, individuals rarely have to consider their identities. But, when these two identities are at odds, this is the space that many bi-racial people find themselves.

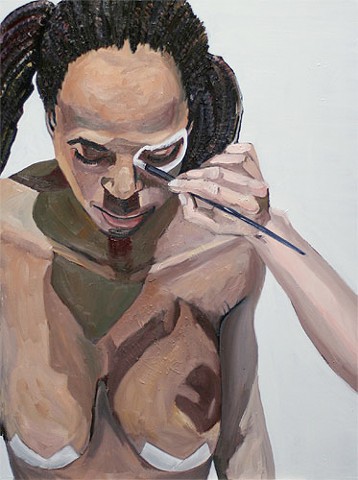

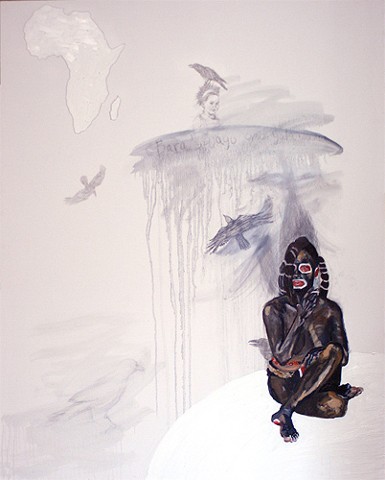

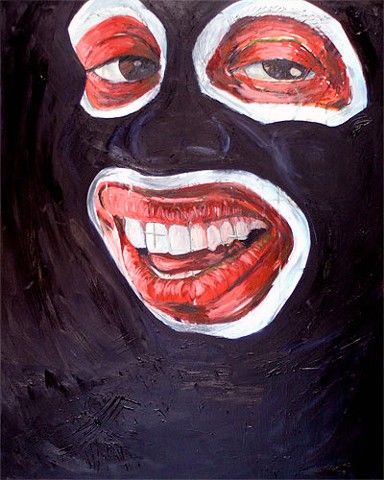

In choosing the imagery, I was interested in showing some sort of transformation. I was interested in the process of revealing and the process of covering up the self. This mask becomes the perceived, or imposed, identity. Onye's mask references an American historical tradition, that of the blackface minstrel. This black minstrel is a chatacture of the field negro or slave on the southern plantation during Antebellum Slavery. This tradition is based on oppression, disenfranchisement, marginalization, and racism. Out of this tradition comes the black sambo. Sambo is made up of the colors black, red, and white. Sambo is a derogatory caricature of a black male. He can be found in early American kitch, cartoons, and children's toys. Another figure that Onye references is that of an Afro-Caribbean deity named ellegua. Ellegua's colors are also black and red. Ellegua comes from an African tradition. He is the keeper of the crossroads. He becomes a symbol of how being bi-racial is like having both feet in two different cultural worlds. Bi-racial people are also keepers of the crossroads of race. These current and historical icons are interwoven into a new character that inhabits the canvas space. This new character is both American and African; derogatory and empowering; white and black; new and old.

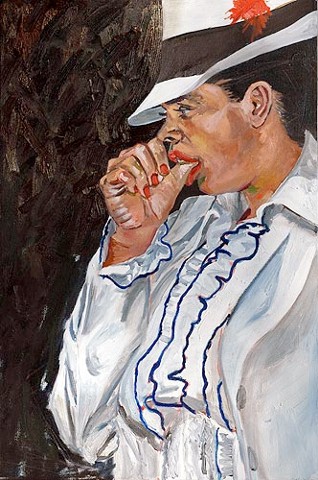

The final character is that of the Black Dandy. This character also found its way into the minstrel show and was a figure that represented the newly free black slave entering the work force. This figure was used to unite the Northern working class against blacks and reinforce the idea that blacks didn't belong. The Black Dandy is the Northern version of the Southern Sambo.

I have woven my experiences into the drawings of the paintings and the titles. I have included a portrait of my mother, who raised me, and my father, who I have never met. They become symbols of two different worlds coming together. They are icons for a new group of people. They symbolize the present, the past, and the future.

To better understand the context of the work the following terms may be helpful:

The minstrel show, or minstrelsy, was an American entertainment consisting of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music, performed by white people in blackface or, especially after the American Civil War, African Americans in blackface. Minstrel shows portrayed and lampooned blacks in stereotypical and often disparaging ways: as ignorant, lazy, buffoonish, superstitious, joyous, and musical.

Blackface is a style of theatrical makeup that originated in the United States, used to take on the appearance of an archetype of American racism - that of the darky or coon. In the United States, blackface was most commonly used in the minstrel performance tradition. White blackface performers in the past used burnt cork and later greasepaint or shoe polish to blacken their skin and exaggerate their lips, often wearing woolly wigs, gloves, tailcoats, or ragged clothes to complete the transformation. Later, black artists also performed in blackface.

Sambo is a racial term for a person with mixed indigenous and African heritage in the Caribbean, also for a Black, or South Asian person in the United States and the United Kingdom. It is considered a racial slur in the US and UK but not in the Caribbean. Several origins of the term itself have been proposed, but it gained prominence through the children's book The Story of Little Black Sambo by Helen Bannerman, in 1898. It was the story of a boy named Sambo who outwitted a group of hungry tigers. The book contains many Caribbean references. Examples of "Sambo" as a common slave name can be found as far back as the 18th century.

In Yoruba mythology, Ellegua is an Orisha (spirit) associated with "opening the ways", or crossroads. Often depicted as a child or a small man, he is a playful and a trickster god. Santeria practitioners often have an Ellegua head behind their front door as he is said to protect the entryway and prevent harm from entering the dwelling. In the Ifa tradition practiced by the Babalawo, ellegua is used to open the way for the god of prophecy Orunmila. Ellegua's fills a similar role in Santeria as Papa Legba in Vodou.